There are many kinds of murder; some are slower than others.

Content warning: This essay contains discussion of multiple kinds of death, bodily fluids, and cancel culture.

If uncle Hugh’s story speaks to you, please consider making a donation to StackUp.org by clicking here.

For the month of September, I will match every donation readers make up to $1,000 – let me know by leaving a comment here or sending me a DM / tagging me on Instagram or Threads.

The last text messages and calls logged in Hugo “Hugh” Richter Wiegand’s phone were on the afternoon of September 24th, 2022. At some time between that point and the evening of September 26, 2022, Hugh died at the age of 53 in his apartment in Tempe, Arizona.

A piece of paper found on his coffee table included a few important handwritten notes: the passwords to his phones and his laptop, that he didn’t want a big funeral, that he wanted his body donated to science, that he loved his family very much, and that he wanted his wife to know what happened.

While the toxicology reports are not back yet, available evidence suggests that Hugh had acquired a number of fentanyl tablets which he ground into powder. Funneling the powder into a pint glass, he added a healthy amount of tequila, and then ingested the cocktail while comfortably reclined on his couch. There were no outward signs of violence.

And while the investigation into Hugh’s passing remains technically open but fairly closed, we can reflect on some other facts about Hugh’s life. These things cannot be fully verified, though; the primary sources are no longer speaking. (Note: the investigation is now closed, but I have chosen to maintain my original words here.)

We know that on May 9, 1989, then 20-year-old Hugh was AWOL (absent without leave) from the US Navy. A bit before 1 a.m, he had turned himself in to authorities at the San Ysidro border crossing at the California-Mexico border.

In an LA Times article from May 10th, Los Angeles Police Department Lieutenant Ron Larue told reporters “(Wiegand) was going to go into Mexico but decided instead to turn himself in,”

In that same Times piece, it’s reported that LAPD officers had found the body of 25-year-old Allison Billard dead from multiple stab wounds in her North Hollywood apartment on Kling Street at around 11:15 pm on May 8.

We know that during his trial and incarceration, Hugh expressed genuine contrition. He pled guilty to Allison’s murder, and spent over 25 years of his life incarcerated to pay his debt to society.

After his release, the contrition remained, but Hugh also looked forward to contributing to society. He wanted honest work, and honest pay.

In the years following, he bounced around the American West: California, Nevada, Utah. He made a few new friends. He rode his motorcycle thousands of miles.

In January of 2022, Hugh settled in Arizona after landing a dream job – one that paid well, and allowed him to use his brilliant and eager mind.

In July 2022 he was laid off from his dream because “he was the most expensive employee.” Despite this, Hugh still took calls from the person who had replaced him. She was lost in her duties, and he was the only one who would help her out.

While taking these calls, he put out over 400 applications to find a new job. He didn’t hear back from any of them.

We know that Hugh’s incarceration had taught him a number of lessons that were hard to unlearn; he was incredibly hard on himself, and sometimes incalculably stubborn.

We know that Hugh loved his family, despite having an incredibly rough childhood. The youngest of 4, he never wanted to be a burden or a disappointment to anyone.

We know that, when interviewed by the Tempe Police Department, Hugh’s neighbors had nothing but great things to say about him. They regarded him as a kind man; a gentle giant. He was always willing to help move something, or to dog sit, or to watch a Raiders game with you.

I arrived at my uncle Hugh’s apartment in the mid-morning of October 1, 2022 enveloped in a mix of emotions. There was sadness that I had not gotten to know him more. There was gratitude for the conversations we had over the years. There was anticipation because I would be meeting Hugh’s brother – my other uncle – for the first time in real life.

There was caution, because it had been decades since I had been in the house of someone who had recently committed suicide, let alone a family member who had done so.

Within half an hour of my arrival, everyone else had materialized, and we advanced on Hugh’s apartment together.

It was remarkably clean; both physically and emotionally warm. Everywhere, it was clear that Hugh had taken great care to prepare his home before his death.

On his desk was an accordion file with all of his important documents and deeds.

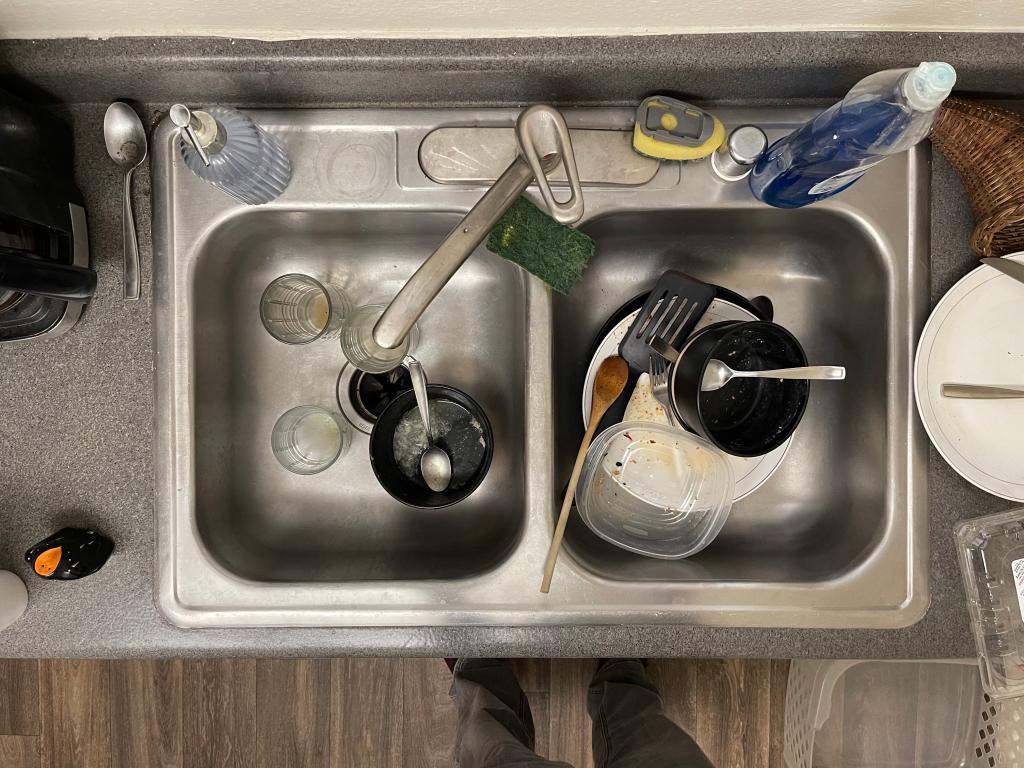

In his kitchen, there was a note about how old the meat in the freezer was.

In the living room, there was a cooler with beer arranged in it.

Hugh wanted to make this as painless as possible for those who showed up for him. He did a great job. I can even forgive the dishes that he left in the sink.

Hugh had a sectional couch, with a long chaise. He loved laying on that chaise so much that he picked it as his final resting spot.

When we moved that couch, my heart broke.

Let me walk you through what you’re seeing. I didn’t know what it was at first, either. This stain with a fur accent was directly underneath the chaise section of Hugh’s couch.

The fur was easy enough to figure out; Hugh’s neighbor Manny would often visit with his husky-mix dog.

The stain gave all of us pause, though. The wipe mark at the bottom roughly coincided with where the edge of the chaise was; we surmised that Hugh had cleaned up whatever made the rest of the mess.

My uncle looked at the stain. Realization hit. He spoke:

“Oh. It’s blood.”

My uncle made his way to the patio for a cigarette.

I crouched down. He was right. It was blood, with a bit of bile. I touched the effluvia; the last part of Hugh’s physical being that I would ever have contact with.

The contrast cracked me. My first tears came while considering that even in death, Hugh lavished us with care, but that in life, he did not allow himself the same compassion.

Speaking to my mother, Hugh’s sister, I later found out that Hugh had been coughing up blood for weeks before his death. He had refused to see a doctor.

Before Hugh died, he was delivering parts for a friend’s business a couple hours a week, getting paid under the table. I think about this, and I think about the 400 applications he filled out, and heard nothing back on.

Was it ageism?

Was it a gap in his employment?

Was it fear of his gigantic 6-foot-4 frame, visible on social media?

I can come up with any of a number of potential reasons, but I know I’m hiding from the real culprit. A basic background check ties Hugh to scarlet truth: California Penal Code 187.(a):

“Murder is the unlawful killing of a human being, or a fetus, with malice aforethought.”

While it’s true that 37 states have some form of ban-the-box laws on the books, justice-involved people who have paid their dues still face an uphill battle.

For instance, in Arizona, while public sector jobs are banned from asking for applicants’ criminal history on a job application, private employers have no such restrictions.

At the federal level, the Fair Credit Reporting Act provides that any arrest not resulting in a conviction more than 7 years back not be reported, unless the applicant is applying for a management or executive-level job, or will be making more than $75,000 a year.

Hugh lived in Arizona. Hugh was management material; he had an MBA and experience.

He also had a murder conviction.

In the weeks since his death, I’ve learned a grim truth. There is a version of cancel culture that many justice-involved people (e.g. felons) are subject to.

In a muted in-person mirror of dysregulated digital lynch mobs, many freed felons encounter potential employers more concerned with effecting further retribution than acknowledging rehabilitation.

Something in these dark souls is satiated by focusing on the failings of the felon, and in turn disallowing them the space and grace to be anything more than what they’ve done – or what the potential employer *fantasizes* the felon has done.

In short: I now know that serving your time does not mean you will be free. The righteous-but-hollow ardor of others crafts a callous, invisible prison.

I fully admit – when I first met Hugh, I feared him. I understand the impulse to be afraid of people with a history of violence, especially those who look like they would be good at it.

Yet my guarded fear did not walk alone that day; it came with curiosity, and openness. It came with the space to hear him tell his story in his own voice; to afford this man the dignity of his full humanity, to see him as more than a sliver of his history. I have my late father to thank for teaching me how to do that.

By no means was Hugh a perfect man, but by all accounts, he had settled his debts to society the best that he could. He had taken time to better himself in prison, honing his spirit, skills, and mind. He earned degrees both inside and beyond his incarceration. He learned trades. He was honest. He did not hide from his past.

He cared about others, deeply. He loved his family, especially his sisters and brothers.

I imagine what he’d gone through since July: he’d lost his dream job, after getting on his feet for the first time since his release.

I imagine him asking his siblings for help, knowing that he needed more than he told anyone.

I imagine him filling out 400 applications, knowing that there’s a good chance few people would see him as more than his worst mistakes, no matter what he had done to atone, or grow.

I imagine him cleaning his apartment while texting people, telling him that he loved them.

I imagine him setting out beer for the guests he knew would arrive soon, but he wouldn’t be there to meet.

I imagine his giant frame falling still on his couch, peacefully, while his blood and bile dry beneath him.

I imagine that now, finally, he is feeling a modicum of relief.

Good night, Hugh. You’ve earned your rest.

1968 – 2022

One thought on “Death Notes: Under the Couch”